Genetic Relatedness Comparison

Genetic relatedness – sounds straightforward, right?

It means that two dogs have many of the same exact versions of genes (alleles) at the exact same places in the DNA (one place is a ‘locus’ and two are ‘loci’.) Usually animals have similar alleles in many of the same loci because they are immediate family. However, when a gene pool has been closed a long time, the chances of having similar alleles in the same places even when there is no close familial relation gets higher and higher. Two dogs with all the same ancestors in, say, the 15th generation can have very similar genes or not so similar genes. When the same traits have been selected for in each of those 15 generations and there’s been regular inbreeding along the way, the chances of those distant cousins having many the same genes is very high.

When that happens, a very distant cousin can be genetically as close as a first cousin, a half sibling, or even a full sibling.

How is this possible? Because genes don’t mutate that fast. Over thousands of generations, there’s a lot of mutation, but over 20 or 50 generations, there’s barely any. So assuming there have been no outcrosses, the genes that were in these closed populations in the 1960s are the only ones that can exist in the dogs today. Yes, there will be a few mutations, but very few, and not enough to change a population, especially if the same traits are selected for over and over and over. This is why today, we breeders have to manage our gene pools very carefully. Selecting for the same traits as described by a breed standard ( which is what we are supposed to do) can inadvertently eliminate too much diversity.

Our predecessors did not know anything about this. Their aim was to breed out bad genes and double up on good genes – a super simple concept, that was really too simplistic. They had, as it turns out, only a very primitive idea of how genetics works, because it’s terribly complex, and thought we have lots more to learn, we know infinitely more now than they did then.

In nature, breeding is usually random and usually based on natural selection. The animals best suited to their environment tend to be the ones that survive in each generation, and harsh natural environments make certain that only the best suited do survive.

For domesticated animals, we humans decide who gets bred to whom, and we base our choices largely on our own personal preferences. That’s true for dogs, cats, and livestock of course, and it’s called selective breeding. If we put them all in a large pen and let them decide who to breed to for themselves, that would be called random breeding. And if we did that with dogs, we’d quickly lose all the traits we love so much in each of our breeds, and dogs would revert to generic village type dogs. This is because dogs, given a broad choice, will instinctively select other dogs that are unlike themselves. That doesn’t mean they won’t breed to a relative, given no other choice, but dogs with intact natural instincts are most likely to select the least genetically similar option. Research shows of course that humans, lemurs, wolves, badgers, mongooses, and so many other species avoid inbreeding whenever possible because it’s healthier, and village dogs are much more genetically diverse than purebred dogs, which is evidence of their most natural state.

Purebred dogs, in contrast, from one breed to the next, display different levels of diversity depending on their history. Some are all quite related, like the distant cousins with genes as similar as first cousins, and some breeds include many individuals that meet the breed description but are comparatively unrelated.

Using the data from the UC Davis Genetic Diversity Test, we calculate a Genetic Relatedness value for each dog with each other dog in its breed, and we display these on each dog’s Genetic Relationships page. Anything under 0 is considered unrelated. When these GR values are averaged for each dog, the number can tell you how similar that dog is to the most typical dogs in the breed.

When all dogs’ average GR values are averaged, the result can tell you how close the breed is as a whole. Since under 0 means dogs are unrelated, when that breed average GR is closer to 0, the breed as a whole is more diverse. The farther above 0 that number is, the more likely there was genetic bottleneck that affected the whole breed or a small number of founders for the breed.

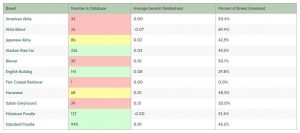

In the screenshot below, taken at time of publication, the breeds with green behind their numbers have enough samples in the database to be reliable, the ones in yellow are conditionally so, and the ones in red are waiting for more data to be entered. We also calculate how many of the dogs are unrelated (GR values of under 0) to each dog, and we average those. The higher the percentage, the more choices breeders have.

Of the breeds in green, we know that Standard Poodles had a major bottleneck, but that there’s ample diversity in the breed overall, so the 0.01 GR average is not a surprise. However, even with a huge sample of Standard Poodles, on average each dog is unrelated to 45.2% of the breed – which means on average dogs are genetically related to 54.8% of them. That average takes into consideration pockets of distinct diversity – many dogs are related to a much higher percentage. But if breeders take advantage of the ability to breed to the least related dogs, there will be an increasing number of unrelated dogs for each choice.

We know the Miniatures are more genetically diverse as a breed, and their GR average is just below 0 (though rounded to zero, hence the minus sign.) Their diversity is more widely spread, which we know from other metrics, and each dog has on average 52.4% of the breed unrelated to them, meaning 47.6% is related.

The Alaskan Klee Kai was founded on 9 dogs, and while we know the breeders have done a good job of distributing that diversity, the amount of diversity remains low. Their breed-wide average GR value of 0.03 is higher than the Standard Poodles, a breed with very badly distributed diversity, and each AKK has on average 43.2% of the breed unrelated to them. That means that 56.8% of the breed is genetically related.

The English Bulldog, with a average GR values of 0.08, also has a very small gene pool. We know from a recent study that the dogs in this breed are closely related, and this is just more evidence of that fact. Each English Bulldog has only 29.8% of the breed unrelated to them, which means on average 70.2% of the breed is genetically related to each dog. They have a very small number of dogs to select from if they want to breed to unrelated dogs.

The Akitas, which don’t have enough data in our database yet (so please send your results in!) show an intriguing trend that would be nice to confirm with more data. The American Akitas look like they are fairly related to one another ( half the breed is unrelated on average) and the Japanese Akitas are more related to one another (42.3% is unrelated on average to each dog.) We know that these two populations have the same alleles as one another, but in different frequencies, and some say these are different breeds altogether. Research shows they are one breed in two varieties, precisely because they have nearly all the same alleles. (By contrast, Poodles and Akitas have very different sets of alleles, both in frequency and in actual alleles.) For Akita “blends”, dogs with some of each group in their recent ancestry, the Genetic Relatedness average is super low – and each dog has a large percentage of the population that is unrelated to it. Strictly from a health standpoint, that shows an opportunity for each population to bring in diversity to their population from the other “variety” without outcrossing to an entirely different breed. Politically this is controversial – scientifically, it’s an obvious choice.

It’s clear from these numbers that it is possible to develop a reasonable picture of each breed as a whole. What’s more, the breed average GR can give breeders a baseline for their dogs and their future choices.

When selecting mates for dogs, it’s important to look for dogs with very low genetic relatedness, but ones that have complementary type. We can see type we like from the outside, and if you are a serious breeder you know what type you want for each breeding. We cannot, however, see genetic relatedness.

Using the GR values, however, there is usually a choice of unrelated dogs for every other dog. Whenever possible, select dogs that are unrelated – we color code those dogs in blue on the Genetic Relationships and Potential Breedings pages. If you want to breed to a specific dog, and its color code indicates it’s as genetically related to your dog as a close relative, only do so if you have a complete history of several generations for each dog, AND if they aren’t highly typical for the breed (you can tell by the Outlier Index).

Also, please only select dogs below the breed average GR. If both parents are highly typical for the breed ( have lower than breed average OI), and you breed them, you are only contributing to depletion of diversity unnecessarily. You might have to look a little harder to find a suitable mate, but each breed has options, and by selecting an unrelated mate you will know at least three things:

- First, you are preserving the existing genetic diversity in your breed.

- Second, you are lowering risks for known or unknown recessive genetic diseases.

- Third, you are lowering risks for complex diseases that may also be lurking in your breed.

Win-win.