Is Diversity testing enough?

A little history: When the Standard Poodle certificates were initially released, we scrambled to understand our results. Did a low IR mean a dog was very different from the population and therefore capable of mitigating our genetic bottleneck, as Dr. Pedersen suggested that we do? What was IR?

We were fortunate at the time to have a group of diversity minded breeders (one of the leaders of which was BetterBred founder Natalie) working together to maintain atypical lines of Standard Poodles and research ways to maintain our breed’s biodiversity. Some of us read the same paper after the release of our results, which compared two different methods of measuring inbreeding: HL (homozygosity by loci) and IR (internal relatedness). We soon came to the realization that IR did not tell us how an individual compared to the population, but rather just gave us information about the “diversity within the dog”. ….What do I mean by that?

In general when people talk about diversity, they are talking about two aspects: diversity within a single dog and diversity within the breed itself (biodiversity).

When we talk about diversity within the dog, we are assessing how much of the genetic material they inherited from their sire is exactly the same as the genetic material they inherited from their dam. When a dog inherits too many of the same genes from both parents, we call them inbred. It’s well known that inbreeding can cause many issues in populations and therefore breeding for heterozygous, or outbred, dogs is encouraged (but remember: linebreeding does not always mean inbreeding) . Inbred dogs also are more likely to express any hidden recessive component diseases and be affected by the disease. You can read more about those concepts here.

I remember opening my email and looking at the pretty certificates and being delighted to see my recent keeper had a very low IR. In our email chain of messages, we thought that meant she was very unique compared to our population (remember, this was a time before BetterBred and our handy mini course!). We had our own software that would predict the IR in litters and help us select for outbred litters. Despite the fact she had a low IR, I couldn’t find many dogs that would produce litter predictions with low average inbreeding. Why, if she was so outbred? Because breeding for diversity it isn’t just about inbreeding; it also matters where a dog fits in the population.

Let’s take a look at her genetics.

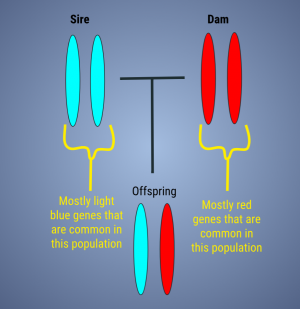

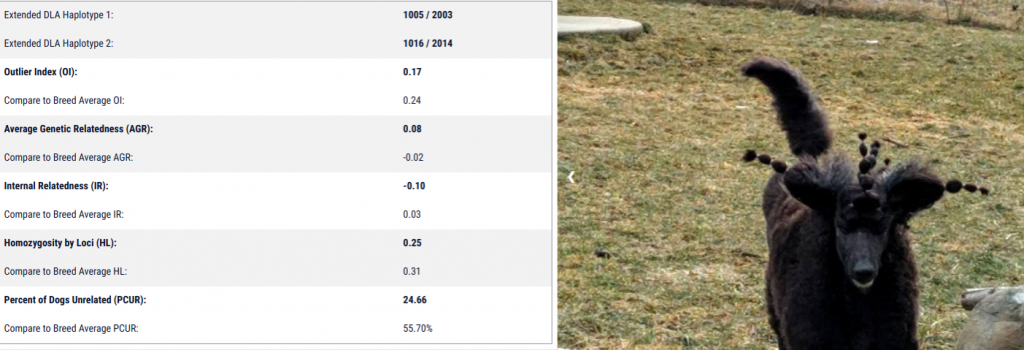

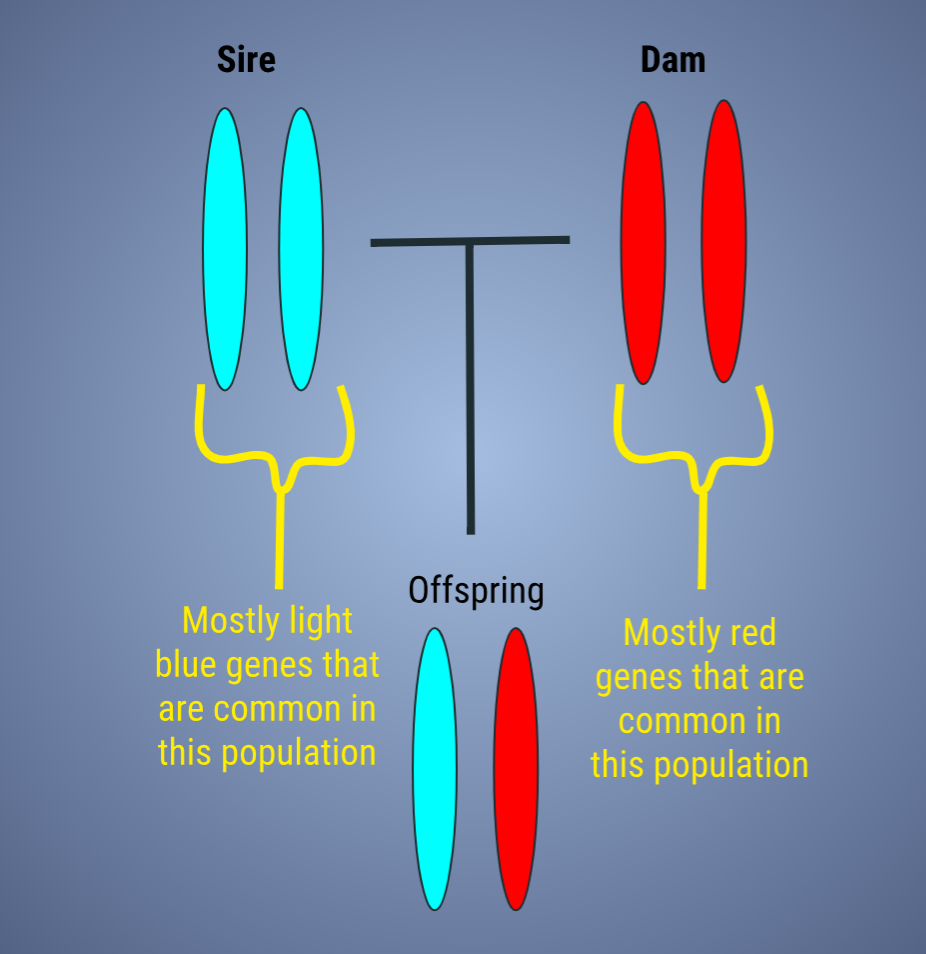

My girl IS very outbred, with an IR of -.10. But the percentage of the tested population that she is unrelated to is only 24.66%, while the average of the breed is 55.7%. What? Let’s talk about her breeding: she was the product of common parti (bi-colored) lines bred to common red lines. What might this mean? Well, her parents WERE unrelated (relatively speaking) to each other, but both were fairly typical for the breed. This means that while she is outbred herself (she received different genetics from her sire and dam), most of the genetics she received are very typical for the breed as a whole, making her related to many dogs in the population.

Looking at her profile, you also see that her Outlier Index is .17. What is this measurement? Outlier index assesses exactly what we discussed above! Namely, it analyzes how common or uncommon a dog is based on how common or uncommon for the population each allele carried by that individual is. As this number becomes lower, a dog carries more and more typical alleles for that population (you can see this under advanced analysis if you are a full member). In her case, she has more typical or commonly occurring alleles than the average Standard Poodle; the average OI for all tested Standard Poodles at this time is .24.

Similarly, her average genetic relatedness is very high compared to the breed average (.08 vs an average of -.02). Average genetic relatedness is a measurement similar to the

pedigree based calculation “mean kinship,” but uses genetic data instead. This means she is more closely related to other Standard Poodles in the database than the average Standard Poodle.

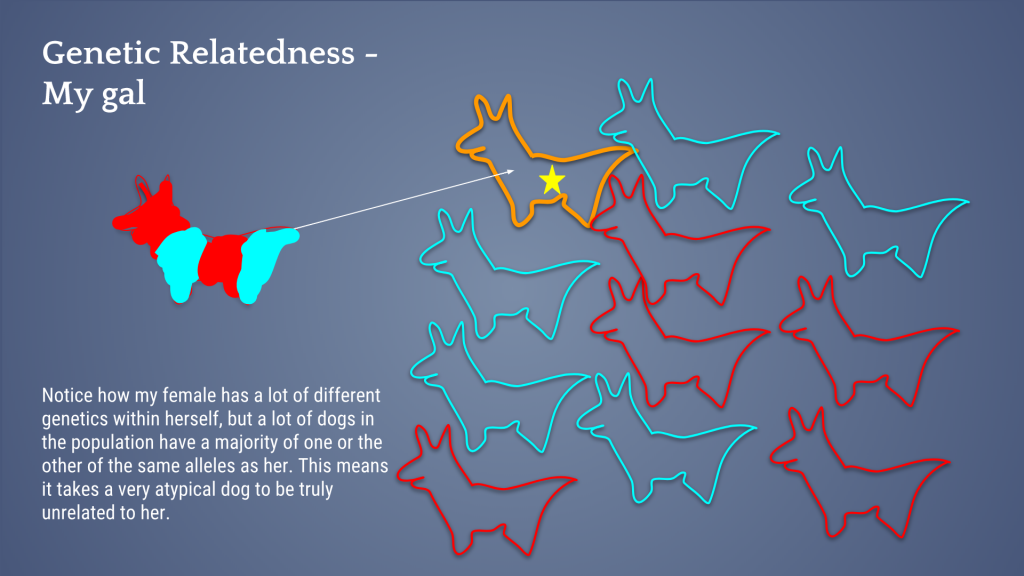

Let’s take a look at a visual of my gal and her “outbred-ness”; the images below demonstrate why she is genetically related to a lot of the population.

Here we see two unrelated parents are bred together, but both with different common genetics for the population (image to the right). The result is an offspring with low internal relatedness. She is outbred, but carries a lot of typical genetics in relation to this population.

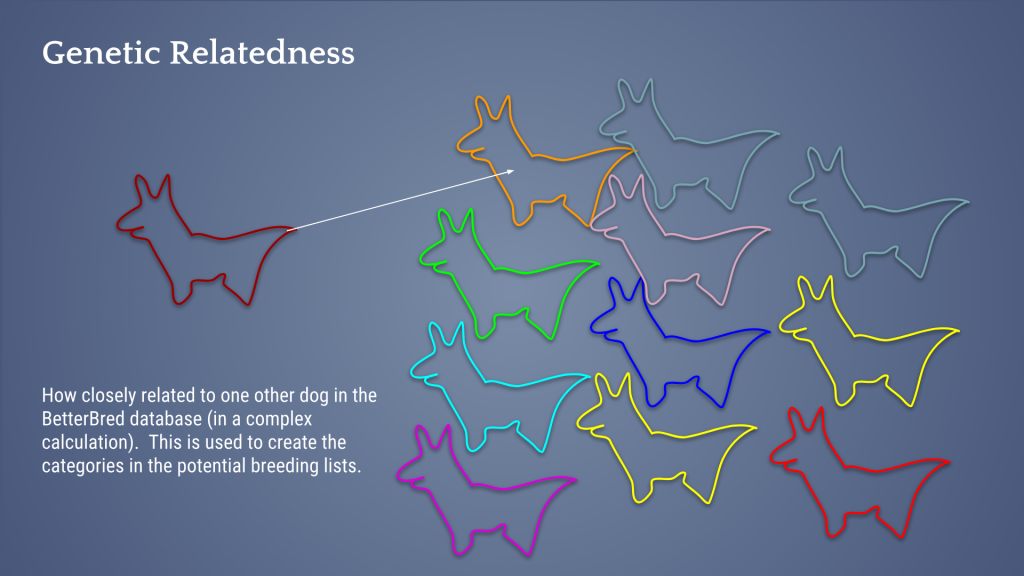

So then, we look for mates for this offspring. Notice in the image below that my female (excuse my dog-llama drawings) has a lot of heterozygosity – or the different genetics inherited from each parent – within herself , but many dogs in the population also have a lot of the same alleles as she (red dogs and aqua dogs). This means it takes a very unusual dog to be truly unrelated to her (orange dog).

My bitch, without further analysis, would seem like an ideal breeding candidate because she herself is outbred. However, once analyzed, I found that she is highly related to a large portion of the population and therefore it’s very difficult to find unrelated breeding mates for her. Indeed, when I looked in the database, she was very hard to find mates for that would breed away from the breed’s genetic bottleneck AND produce outbred puppies.

So what did I do? First of all, of course I considered type, temperament, drive, pedigree and health just as I always have; I looked for mates that would move my program forward in all regards that define my program goals. For her first breeding I compromised on the inbreeding values in the puppies; I sacrificed a higher IR in the puppies in order to breed away from the genetic bottleneck (since our breed specific diseases are correlated to our genetic bottleneck). For her second breeding, we found a boy in Poland – who was subsequently imported to the US – who was both genetically different from the population AND from her. Without our breed management software, I would never have known how closely related she is to other dogs in our breed.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post