Standard Schnauzers are now enrolled at UC Davis for genetic diversity testing.

Genetic diversity – this is a term that often can be confusing and frankly a bit intimidating to breeders. For example, some people refer to outbred dogs, or dogs whose genetics received from their dam are very different from the genetics received from their sire, as “diverse.” While that might mean that a dog has a lot of diversity within itself, it does not describe the population as a whole or where that dog fits into the population. Does that dog carry genetic markers that are very typical or atypical for that population? And why does this even matter?

In population studies, one way to assess the overall genetic diversity – or genetic state – of a breed is to look at, overall, how inbred the entire population is. In general, the more inbred and genetically similar a whole population is, the less genetic diversity the breed has. As breed-wide genetic variation – or biodiversity – decreases, the harder it becomes to find unrelated or less related mates to which to breed.

Why might we want to find unrelated mates? Because, as a gene pool shrinks, breed specific diseases (many times with complex genetic contributing factors that are difficult or impossible to develop a diagnostic test for) often become “fixed.” Fixed disease means all dogs in the population have some or all of the genes necessary to develop that disease and so are at risk. So, even in breeds where there are no pressing breed specific diseases, we don’t want them to develop. We want to safeguard our biodiversity as best we are able to prevent the rise in frequency and potential fixation of them.

Another way to assess a population is to look at how much variation a breed has at neutral markers (markers that do NOT code for known traits in a dog) and then also to look at how well distributed those markers are within the population. This estimates the range of biodiversity, or allelic richness, of a breed.

BetterBred founder, Natalie Green Tessier, describes this natural variation, or biodiversity, with the following simple example:

“Most breeders think of DNA as coming in two options- a good gene, or a mutant gene – like it is in many DNA tests. In fact, there are many genes or (in this case) markers that come in a great many variations – like a t-shirt that is available in different colors. The more variants there are, the more information we have about population genetics. In more inbred breeds, there are fewer variants for each marker. So an inbred breed might have only a few colors in t-shirts available, whereas a diverse breed will have many colors of t-shirts. Apart from the relatively small number of genes that make up breed traits, the rest of the gene pool is generally healthier when there’s lots of variation.

Unfortunately when breeders select too strictly for too long for very specific traits, there can be an unintended loss of variation in the parts of the DNA that thrive with more variation. A good way to assess whether that good variation has been impacted is using the markers found in the VGL canine diversity test. Because they are considered neutral – or not associated with any specific known trait – they are great for a check up on genetic diversity. In breeds with ample diversity, there will be lots of variations for each marker (lots of colors in the t-shirt drawer.)

But what if you have a breed without much variation? Well, this happens, and can happen quite often. In this case the best thing breeders can do is try to make sure the variants that are in the breed are well distributed – so there are plenty of all of them in the breed. Imagine a t-shirt drawer with lots and lots of red t-shirts and only one blue one and one green one. If you lose one of the red ones, it doesn’t change much about the t-shirt drawer – there are lots of other red ones. But if you lose either the blue or green one, the variation is seriously diminished. If, on the other hand a third of the shirts are red, and a third are green and a third are blue, then it’s a lot harder to lose the existing variation in the drawer, even if you lose one once in a while and even though there are only 3 colors.”

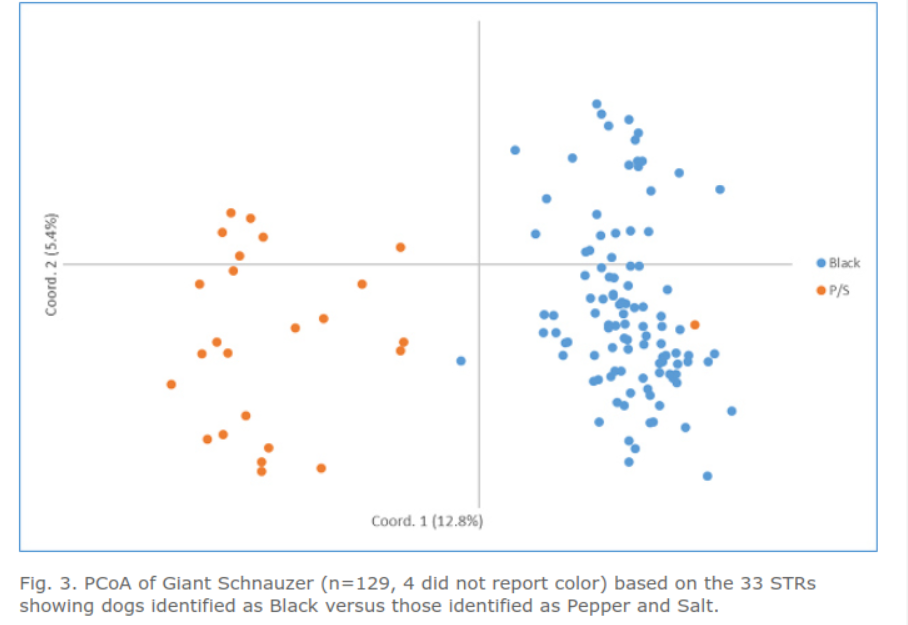

So, once this information is established for a breed, how do breeders use it? The genetic diversity testing will provide breeders with the ability to use their individual dog’s analysis to breed for the retention of the existing biodiversity in the gene pool and understand genetic relatedness among the dogs in the population, as well as breed for outbred puppies. Some people discuss genetic diversity in breeds as if the sky is falling – but in reality many breeds are in relatively good shape and we just need to safeguard the retention of our biodiversity for future generations. Giant Schnauzers are a relatively small breed in numbers, so they were not found to be the most diverse breed yet tested genetically, but they have average biodiversity in comparison to other breeds with very typical distribution of that biodiversity. Breeders have been managing the ones tested fairly well, but VGL testing helps them ensure their line breedings won’t get too close (before the breeding!) and that their outcrosses are really outcrosses. We don’t yet know the genetic status of the Standard Schnauzer, but we are excited to see what’s there. Should any breed be shown to have a genetic bottleneck due to popular sires or fall in popularity, this testing can help mitigate it.

What information does a breeder get about their individual dogs?

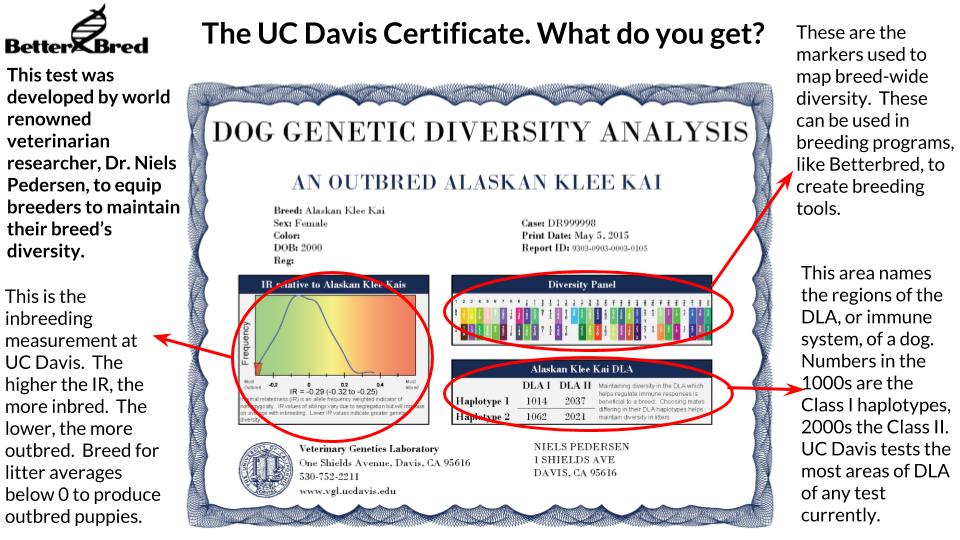

- An inbreeding estimate, called IR, for the individual dog.

- DLA, or Dog Leukocyte Antigen, results – this is the immune system of the dog. Likewise, the more biodiversity in a breed’s DLA, in general, the healthier the breed.

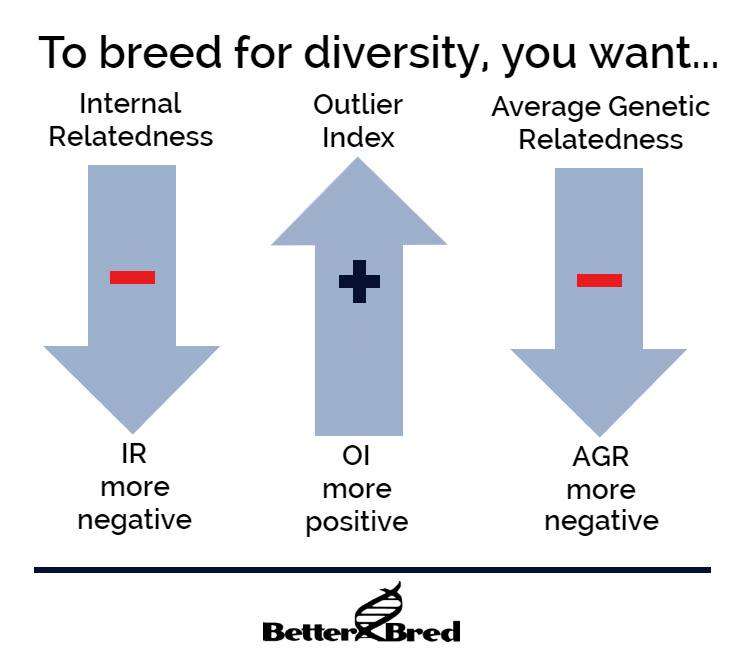

- Upon upload to the BetterBred database, individual dogs will be assessed for a measurement that tells you how closely related your dog is to all the other tested dogs in the database. This measurement called Average Genetic Relatedness (AGR) is similar to the pedigree based measurement called Mean Kinship (mk).

- Upon upload to the BetterBred database, individual dogs will be assessed for a measurement called Outlier Index (OI). Outlier Index tells you how typical or atypical a dog’s genetic markers are in comparison to the tested population.

- Dogs can have titles, health testing, and a photo uploaded with free storage on BetterBred.

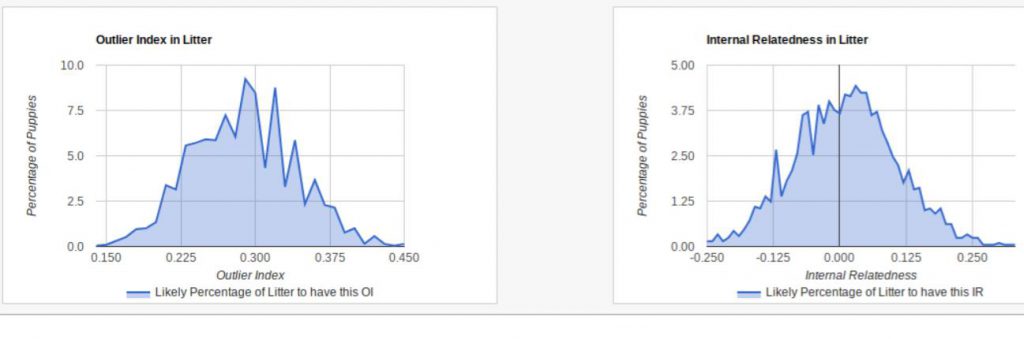

- Breeders will have access to breed management software and breeding lists to plan litters in order to maintain the breed’s existing biodiversity. Test breedings can assess both the range in inbreeding in a litter as well as how a genetic range for how atypical or typical for the breed the puppies will be; by using this, breeders can contribute to breed biodiversity retention and understand how closely dogs in the genepool are related to one another. Breeders who participate in the initial analysis are not required to participate in the software subscription; all participants will be offered a free trial to the breed management software.

With the above, breeders will have the ability to use their results to know just exactly how genetically related dogs are to one another within the population. Most breeders are aware of COI – but VGL testing can tell you more accurately how inbred your dog is. It can also show how genetically similar your dog is to an ancestor – provided both are tested. Want to line breed to set type? Check how closely two relatives are from one another, and select the least related that meet your goals! Have a long lived ancestor? See how closely related the puppies in your litter are to that bitch! Have two puppies you are considering keeping? Test them to see which preserves biodiversity in the breed most (you’d be surprised how different siblings can be from each other!).

What does it cost? Each individual dog’s test costs $50 during the research phase. This entire fee goes to UC Davis to fund the laboratory associated costs for breed analysis and individual dog testing. After the research phase the test cost goes up to $80.

Some people fear that “genetic diversity” is a buzzword that gives people justification to breed dogs that should not be bred or that dogs that are unproven or untested will be bred. While abuse of testing can sometimes happen, the onus is on preservation breeders to breed as they have before – for the correct type and temperament – while incorporating new methods for the preservation of our breeds for our children’s children. We must balance all our tools, just as we always have in the past. This is so much more than breeding for outbred puppies – this testing is similar to methodologies implemented by zoo species management programs. These are exciting times for the dog breeding community!

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post