What’s “enough” diversity in a breed?

In the last decade or so, there have been those who’ve decried the state of purebred dogs, saying they are all lacking genetic diversity, rapidly declining toward extinction and that there is no way a purebred breed with a closed studbook can be healthy. This narrative caught a lot of dog lovers’ imaginations. There’s just enough evidence to make it plausible and audiences love both a doomsday scenario and a hero plot.

There’s just one problem. It’s not true.

Not all breeds are in trouble. Some decidedly are. Some are in a little trouble. Some aren’t at all. We can’t be sure from pedigrees which breeds are really struggling with loss of diversity. Looking for autosomal disease mutations will not solve all the health issues in dogs, and sometimes focusing on them causes a loss of diversity, by encouraging the culling of all “carriers.” Additionally, we can’t tell how best to manage whole gene pools without knowing more than pedigrees.

Why is that? Because even if the last 5 or 10 generations of a single dog’s pedigree show mostly different names, chances are, at the 15th, 20th and 25th generation the names will be largely the same. Most purebred dogs have all the same ancestors as other dogs in their breed.

Now 25 generations seems like a long, long time, and if we consider that a generation is an average of 3 years, that’s about 75 years ago. It might be easy to imagine there’s been enough genetic mutation in that time period that diversity would perhaps have returned. Nope. Genomes of complex organisms simply do not mutate that rapidly. This is why we’ve found that dogs in some breeds from all over the world that we think may be quite different, really aren’t so different.

Breeds with closed studbooks, therefore, are stuck with what they’ve got. That concept makes some people panic (“They need more or they’ll die!”) and makes some people pleased (“Generations of work to improve them, make them consistent, predictable and historic!”). Objective fact can easily be colored by passion and emotion. The truth is not found at either extreme.

All domestic species, not unlike endangered and captive ones, are caught between these two poles: variation for health, similarity for predictability. Breeders, farmers and conservationists all have the same necessary and collective task of population management, whether they know it or not. All the people who breed specific animals want to preserve their essence, biological or historical, in the form it evolved through either natural or artificial selection. To do that, the population must have some consistency from one individual to the next, enough to make it a breed or a species. Likewise, each population requires enough genetic variation from one individual to the next to remain healthy and adaptable, despite changing environments and other challenges.

Livestock need to be bred for efficient production traits – more milk, more meat, more wool – but they also need enough diversity to have high functioning immune and reproductive systems. Additionally, we want to preserve native breeds that are uniquely adapted over eons to specific environments, and not just replace them with the highest producing breeds which may not be well suited for all environments.

Captive and endangered species can become less viable when re-introduced to their native habitats just by reproducing in captivity or other geographically isolated areas. Without both gene flow and natural selection, captive populations may have become too inbred, or may inadvertently retain genetics that aren’t a detriment in captivity, where their needs are provided for, but which may handicap them and their offspring in the wild. Maximizing retention of existing diversity insures there will always be some individuals with the right genes for any environment.

All domestic species, not unlike endangered and captive ones, are caught between these two poles: variation for health, similarity for predictability. Breeders, farmers and conservationists all have the same necessary and collective task of population management, whether they know it or not.

So while dog breeders and dog lovers may feel like our effort at BetterBred is a singular endeavor, it’s really not. There are lots of people doing what we do, studying the same things we do and trying to do what we do well. What breeders do is manage populations, either blindly or knowingly. We intend to equip them to do it knowingly.

When we do it blindly, we risk making emotion-based assumptions. “My breed is a DISASTER,” or “My breed is JUST FINE,” is what we hear. People identify with one camp or the other and fight for their position, unintentionally impeding progress. Meanwhile, a few more generations of the breed are planned, born and either suffer or enjoy the consequences of their humans’ breeding decisions.

Wouldn’t it be better to take a dry eyed look at the situation from a larger viewpoint and just get on with business?

Here are some concepts that are sometimes debated (see above) but that aren’t actually worth the energy, and really aren’t that debatable.

- Breeds that are recognizable as their breed and have a closed stud book – no matter the range of “quality” within the breed – already have had their diversity limited over many generations, especially in the genetic regions that control breed type (or breed specific appearance and temperament). There is already enough genetic consistency in any established breed to produce dogs with breed type. Breeds do not require any further close inbreeding to “set” that type, because it’s already set. Inbreeding is a very powerful tool, was used to create modern breeds and like any powerful tool can be overused. That doesn’t mean no one should ever linebreed – it means it should be done with much care and awareness of the larger context of each breed.

- Most breeds have a large percentage of very healthy dogs despite any limitation of diversity and sometimes because of it. While breeders selected for breed type, lo, these many generations, they also selected away from weak or diseased dogs or those with inappropriate temperaments. Like inbreeding, outbreeding is also a very powerful tool, may not be a magic cure for a singular problem, and often brings with it other surprises. With increased genetic variation, there will be an increase in need for selection, requiring a keen eye and clear idea of functional breed type and, in some instances, sophisticated meaningful diagnostic measures that differentiate between healthy and not healthy.

- Genetically diverse individual dogs are not inherently better. Some are. Some aren’t. But well managed, genetically diverse breeds ARE more desirable because they tend to have a higher percentage of healthy dogs. Deleterious recessives, known and unknown, stay lower in frequency, are less likely to meet up in individual affected dogs and complex genetic diseases are less likely to become highly frequent or fixed in the breed. Immune function tends to be better in more individuals, reproduction more successful and newborns less likely to die.

- Extreme traits are not good breed type. Any trait can be taken to an extreme and every litter has a range of traits. Selecting the most extreme type from each litter over generations may or may not impact genome wide diversity in the breed, but it certainly can lower the frequency of the relatively small number of genes for moderate type in a breed. Once those genes are bred out of a closed gene pool, the only way to get them back is to outcross. If people don’t want their breed outcrossed at any time, they should consistently select for moderation. What constitutes the difference between extreme and moderate type is a matter of function and it’s up to breeders to assess. They know what’s what and should guard against any “kennel-blind” instincts that excuses ill health or dysfunction.

So now that we’ve covered those bases, let’s talk about practical realities. It’s all words until you have a decent analysis of your breed. Fear mongering is as futile as putting our heads in the sand. Let’s just do neither.

What do we need to know as breeders about our breeds?

There are two factors that determine whether a breed has retained diversity or not.

First there is the number of founders. Lots of founders mean that there was lots of genetic variation in the breed at the beginning and therefore a large palette from which to select. It also means each founder’s individual strengths and weaknesses can have a smaller long-term effect on the breed. If one founder had a great coat but a less-great heart, breeders could more easily keep the good coat traits and breed away from the bad heart traits because there are plenty of other very different dogs in the generation. By contrast, very few founders mean each founder has a very large impact on the breed, so it might be more difficult to keep those great coat genes from that founder without also getting too many of those bad heart genes.

Second, there is the way the breed has been managed since its founding. It should be clear by now that how we select our next generation – and how closely related our breeding pairs can safely be – is influenced by how much diversity remains in the breed. It’s also influenced by how, over the generations, breeders collectively chose their breedings and pups to run on. If they inbred significantly over long periods, we will have to be very careful. If they didn’t, we have more wiggle room. If they focused solely on type, there might be one outcome, or if they focused on more complex working abilities there might be another. If there were multiple endeavors, there could be yet another outcome. If their dogs were pampered or lived in harsh conditions, their selections will have had an impact. If there were a few super popular sires or kennels, a breed with many founders could nevertheless have dwindled down to quite a genetically depleted breed. If a small, quite specialized breed with just a few founders was bred for hardiness out of necessity, there might be little overall variation, yet have low frequency of disease genes, and very moderate, functional type.

How do we breeders assess our breeds in a way that helps us make better breeding choices? We pay attention to these two factors: overall genetic variation, and homozygosity. Variation is what we have to work with, homozygosity shows us how well we are doing with what we have.

So, how is YOUR breed doing?

To illustrate that, let’s take a look at a few very different breeds. They are from a wide range of origins, purposes, phenotype and breeding cultures. Working and companion, large and small, common breeds and unusual ones – they all have different combinations of genetic variation within the breed and differing levels of breed-wide inbreeding.

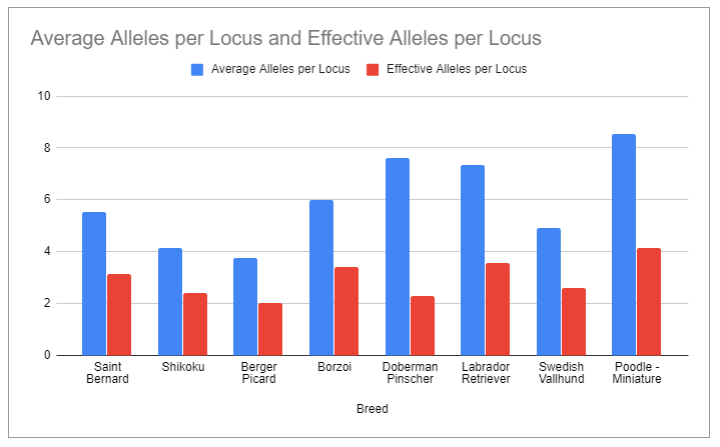

The blue bars (average alleles per locus), seen in Figure 1 to the right, show how much existing genetic variation is found in the breed, while the red bars (effective alleles per locus) show how much of that variation makes up the vast majority of the breed. Very generally speaking in our observation, the overall healthy breeds, ones with longer lives and no crisis-level breed specific diseases, seem to have about half the existing variation well distributed in the breed. That means effective alleles are at least half the average alleles, or in the graph below, the red bar is half-way up the blue bar. (Of course there are always exceptions; sometimes a breed has either so little diversity or so much disease or dysfunction that good breed management will not be enough to help, but that is rare, and even then good breed management is still better than poor breed management.)

As you can see, the Miniature Poodle has the most variation (blue bar) as well as the most well distributed variation (red bar). The Berger Picard has the least variation, which is to be expected because it purportedly came from two dogs. But breeders in the Berger Picard breed are doing a decent job of using the variation that exists. Compare that to the Dobermans, which have the second most variation of these breeds, but the second least well distributed variation. This tells us that Dobermans have a breed management problem, while Bergers Picard vulnerability is more due to lack of variation in the breed.

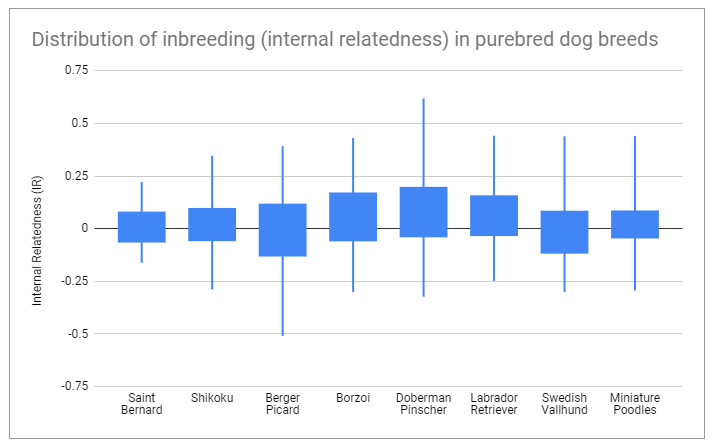

Next let’s take look at inbreeding. Figure 2 shows more about what kind of breeding choices breeders are making.

To understand this chart you need to know that the middle block is where most of the IR values are for the dogs, and lines represent the extremes of inbreeding and outbreeding in the breed. A flatter block means more of the tested dogs fall within a more narrow band. A taller block means the bulk of the breed has more range of inbreeding. Ideally the block would be centered on zero and fairly flat, meaning most of the dogs are not being more inbred than the breed already is due to historical breed formation. This collective activity by breeders is most likely to maximize retention of the existing genetic variation within the breed.

The blocks that are taller and are mostly above zero are being inbred further than the breed already is. That means that there is going to be more loss of existing genetic variation, which can put a breed further and further at risk of increase in breed-specific disease, and less reproductive success.

The tail lines show us the extremes in inbreeding and outbreeding being done in each breed. Dobermans have both the most inbreeding in the bulk of the breed (the middle block is mostly above zero) and the highest extremes of inbreeding by far. This is what is causing the low effective alleles in the breed in the graph before. The Doberman population also has several very serious breed specific diseases that are extremely difficult to avoid when making breeding choices.

It is interesting to note, too, that Miniature Poodles and Labrador Retrievers, while being breeds with vast genetic variation, have many highly inbred individuals and their blocks are also more above zero than centered on zero. Comparing them both to the Swedish Vallhund, which was documented to be founded on only 5 farm dogs when the breed was restored, the Vallhund breeders are doing a better job overall of not losing what they have. They, too, have some highly inbred individuals, but overall, they are clearly making better choices to best retain existing diversity.

A very interesting set of data in this graph is what we see in the Berger Picard. A working breed decimated by the impact of two brutal wars fought in its native region of Picardy, France, the amount of diversity found in the breed is extremely limited. However, it appears from the well balanced bulk of the breed with a mean inbreeding value hovering at about 0, and some extremely outbred individuals as well as inbred ones, that this breed is being well managed. That means that collectively the breeders do not seem to be breeding in a way that will hasten loss of genetic diversity in the breed. That breed management may well contribute to the fact that this breed does not have very high frequencies of disease. Like the Swedish Vallhund breed, the modern Berger Picard is based on working dog founders who may have been lucky enough to have had a low “genetic load,” a term meaning the number of hidden genetic vulnerabilities an animal may carry.

These are just two ways we can compare and contrast the data found in our purebred breeds. We can use these assessments as well as a number of others to inform breeders right now about how their breed is faring and how their choices can contribute to preservation of a healthy historic breed.

If you are interested in looking at more of these statistics, you can look at breed comparisons here.

If you are interested in having your breed enrolled so you can see how your breed and breed community are doing, you can learn more here.

Join us in breed management; each full membership helps support BetterBred and our goal of breed conservation as well as our educational tools!

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post